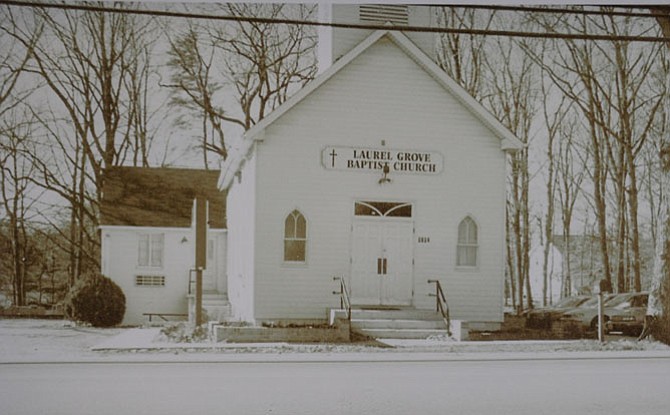

Phyllis Ford grew up in a house behind the Laurel Grove Baptist Church (background, right of the church) on Beulah Road in Franconia. Photo courtesy of The Franconia Museum

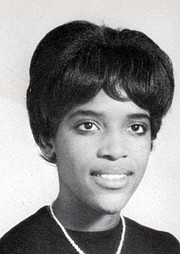

Florence King was pretty impressed with her school bus driver. The Alexandria resident grew up on Old Telegraph Road and rode the bus to both Drew Smith Elementary School in Gum Springs and Luther Jackson High School, prior to desegregation. King graduated from Luther Jackson in 1965.

“It was amazing how the driver knew where every black person lived,” King said. Along the lengthy, circuitous routes to Drew Smith and Luther Jackson, King’s bus would pick up students from pockets of African American communities all over Fairfax County.

White students along the route waiting for their buses were generally respectful, King said, except for a group in the Hollin Hills area, who could yell names and throw eggs as King’s bus passed. “It was awful,” she said. “I think they were just kind of ignorant.”

OPENED IN 1954 to specifically serve African Americans in Fairfax County, Luther P. Jackson High School in Falls Church got its name from the founder of the Negro Voters League of Virginia. Dr. Jackson was also chair of the History Department at Virginia State College.

King’s family was one of the only African American households in their neighborhood. Her great great grandfather was a freed slave from George Washington’s plantation who stayed in the area; her great grandfather was Thornton Gray. She remembers the atmosphere at Luther Jackson fondly.

“It was the camaraderie, the chance to meet people that looked like us,” King said. “We never saw them. It was good to be around my people, thinking: This was fun.”

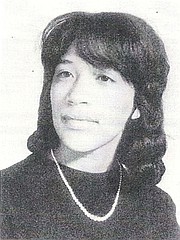

Sandra McNeill’s family moved in near the King’s before the girls were in high school. They became close friends and enjoyed playing in the woods by their houses and picking fresh fruit. When they started going to Luther Jackson together, the same year, McNeill remembers her parents saying the school was separate but not equal.

“We were always told Caucasian kids were more advanced,” said McNeill, who currently lives in Franconia. Her grandmother was a teacher at the historic Laurel Grove Elementary School. “We got their books two years later,” after students at other schools had gotten new books.

Despite having older books, McNeill and King thought they received solid instruction from dedicated and caring, all-African American teachers who also had Ph.Ds in their fields.

“It was above equal,” said King, who confidently rattled off the French she still retains from language labs Luther Jackson students were encouraged to take.

In King’s family, she said, regarding Caucasian students, “they didn’t want to put it in our mind that we’re not as good as they are.”

But in general, King and McNeill said they didn’t feel too threatened from racial tension in their community during high school.

Luther Jackson classmate Phyllis Ford, who grew up around Beulah Road in Franconia, said the Caucasian families in her area were pretty accepting, and that her parents otherwise sheltered her and her brother from protests and Civil Rights issues. “They didn’t talk about it a lot,” said Ford, “we just kind of sailed through.”

Ford’s great grandfather was William Jasper, who after being freed from slavery purchased 13 acres of land in northern Virginia in 1860. Retired in theory, Ford sits on the board of the Franconia Museum, represents Lee district on the Fairfax County History Commission, is president of the Laurel Grove School Association and director of the Laurel Grove School Museum.

FORD WOULD DO homework together with her Caucasian neighbors across the street, students from the Gorham family who attended Edison High School.

“It didn’t feel segregated, really,” Ford said. “We just did it. I wasn’t really thinking about it.”

Their senior year, all Ford, King and McNeill had the option to attend the base school for their area, Edison, but chose to graduate from Luther Jackson.

“The most important thing was to get an education,” said King. “That was your ticket.”

For the 1965-66 school year with desegregation in full effect, students were required to return to their local school. Luther Jackson became an integrated middle school for grades 7 and 8.